Ezra Pound

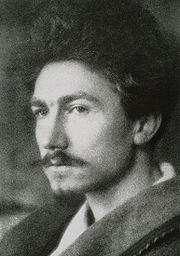

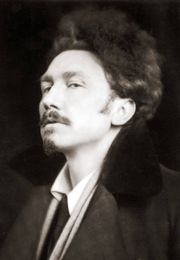

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an American expatriate poet, critic and a major figure of the early Modernist movement. His contribution to poetry began with his promotion of Imagism, a movement which derived its technique from classical Chinese and Japanese poetry to stress clarity, precision and economy of language. From 1912 until the mid-1920s he lived in London and Paris, vigorously promoting the work of the best known modernist writers such as W. B. Yeats, James Joyce, T.S. Eliot and Ernest Hemingway, as well as visual artists including Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and musicians such as George Antheil. His later work, spanning nearly fifty years, centers on his epic poem The Cantos.

Pound was born in Hailey, Idaho, and grew up in suburban Philadelphia, where his father was an assayer at the U.S. Mint. He was trained in classical literature at the University of Pennsylvania and Hamilton College. In 1908 he moved to London, where he lived until 1921 before relocating to Paris. During those years his work included poetry such as Hugh Selwyn Mauberley, articles in magazines including The New Age, and translations of medieval writers like Guido Cavalcanti and Ernest Fenollosa's papers. He moved to Rapallo, Italy, in 1924, where he lived for much of the rest of his life. He married Dorothy Shakespear in 1914; she gave birth to a son, Omar, in 1926. For most of his married life he was romantically involved with the classical violinist Olga Rudge, with whom he had a daughter, Mary, in 1925.

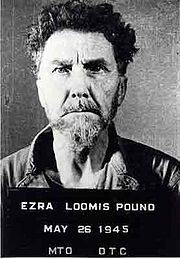

After World War I, Pound became interested in the theory of social credit, which he promoted aggressively during the 1930s. At the same time he attempted to prevent the United States from entering World War II, and began to promote Mussolini's fascism. Between 1940 and 1942, Pound made a series of anti-semitic radio addresses from Rome in which he criticized America, and supported the policies of Mussolini and Hitler. Following his arrest for treason in 1945, he spent almost six months in a detention center in Pisa. For 25 days he was kept in a steel cage, where he had a mental breakdown. During this period he began work on his Pisan Cantos, for which he controversially won the Bollingen Prize. On his return to the United States he was incarcerated at the St. Elizabeths Hospital until 1958. Following his release Pound lived in Italy until his death. He continued to work on The Cantos, which he had begun in 1915.

In the early 1970s, literary critic Hugh Kenner published a book titled The Pound Era, ranking Pound as the most influential poet of the early 20th century. Despite Kenner's attempt to resurrect his reputation based on the theory of new criticism, Pound is the most controversial American poet of the 20th century due to his antisemitism and the charges of treason. Pound died in Italy on 1 November 1972.

Contents |

Biography

Early life and education

Ezra Loomis Pound was born in Hailey, Idaho Territory, to Homer Loomis and Isabel Weston Pound. His grandfather, Thaddeus C. Pound, had mine-holdings in the Wood River Valley; his father was in charge of the United States Land Office, which oversaw mining operations in the area.[1] Hailey was a prosperous western mining town, with a single street, saloon, hotel and newspaper office. Homer built for Isabel the first plastered house in town; however she convinced her husband to leave, claiming the altitude made her sick (Hailey is 5,000 feet (1,500 m) above sea-level). The couple left in the winter of 1887, and according to Ezra's autobiographical Indiscretions, traveled through the Great Blizzard of 1887 "behind the first rotary snow-plough".[2] For a short period in 1889 they moved to Wisconsin to live with Thaddeus Pound before Homer accepted a job as an assayer with the United States Mint in Philadelphia.[1]

The family settled in suburban Wyncote, outside Philadelphia. Pound often visited New York City, and in 1898 traveled to Europe with his Aunt Frank, first to England and then to Belgium, Germany, Switzerland and Italy.[3] After attending public schools in Wyncote until the age of 12,[1] he was sent to the Cheltenham Military Academy, where the main subject was Latin and the boys were made to wear Civil War-style uniforms. He later professed to have disliked the drills.[4]

Pound's grandfather, Thaddeus Pound, was an influential member of the Republican Party: he was Lieutenant Governor of Wisconsin, three-time member of Congress, and candidate for Secretary of the Interior under President Garfield.[note 1] The maternal side of the family was equally influential. Pound's mother Isabel descended from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. His was a family that participated in national politics, felt connected to the centers of power, and was on speaking terms with politicians and leaders. As an 11-year-old, Pound had a limerick published, written in response to the 1896 election.[5]

At age 15 he wanted to be a poet, and was admitted to the University of Pennsylvania where he stayed for two years. He studied literature, history, mathematics, German and Latin, played tennis and took fencing lessons. He became friends with William Brooke Smith and William Carlos Williams (who was studying medicine). In the summer he returned to Europe, visiting London with his father.[6] In 1903, he transferred to Hamilton College, possibly because of poor grades. At Hamilton he was influenced by his professor of Romance Languages and Literature, from whom he had private lessons in Provençal; and he studied Anglo-Saxon and medieval poetry—subjects that were to become a foundation upon which he built his work. He graduated with a Ph.B. in 1905.[7]

After graduation he traveled alone to southern France, Paris, and London.[8] He then returned to the University of Pennsylvania, completing a M.A. in Romance philology in 1906.[9] A post-graduate fellowship allowed him to return to Europe, to study Lope de Vega's plays for a proposed Ph.D dissertation. On his return for the 1906–1907 academic year, his studies focused on the Chanson de Roland, Boccaccio's Decameron and the Provençal poets. He left the University of Pennsylvania without completing his degree or his dissertation.[10] That year he found a "renewed interest" in H.D. (Hilda Doolittle), whom he had met a few years earlier.[8]

He was hired for a teaching position at Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana—a conservative town where he attracted scandal. When he found a hungry and stranded actress on the street in a snowstorm, and brought her to his room he was dismissed from his teaching post.[11] Pound returned to Europe, where he settled in Venice and self-published A Lume Spento, his first collection of short poems. From there he moved to London with the intention of meeting William Butler Yeats.[12]

London

When Pound arrived in London in August 1908, he was twenty-two years old. He quickly found lodgings, a distributor for his book, and a position lecturing at the London Polytechnic Institute.[13] Pound established himself with the literati of London, affecting a flamboyant veneer: he dressed in brightly colored capes and wore an earring and hand-painted silk shirts. Some of his behavior may have been to compensate for insecurities or to present himself as an aesthete—a young man serious about his art. His commitment was realized as he began to see his poetry, reviews and essays published.[14]

| Then came Ezra ... his Philadelphia accent was comprehensible if disconcerting; his beard and flowing locks were auburn and luxuriant; he was astonishingly meager and agile. He threw himself alarmingly into frail chairs; devoured enormous quantities of your pastry; fixed his pince-nez firmly on his nose ... and read you a translation from Arnaut Daniel. —Ford Madox Ford's description of Ezra Pound in 1909.[15] |

That February, at a literary salon, he befriended Olivia Shakespear and her daughter Dorothy. Olivia later introduced him to Yeats.[16] By June 1909 he had met the critic and poet T. E. Hulme, written and had published Personae to good reviews, and was gaining a reputation in the literary world.[17]

He secured a second series of lectures and wrote lecture notes for the British Library that became the basis for The Spirit of Romance (1910). He began his lectures in October—Dorothy Shakespear attended with her mother—and in the same month he had a small volume of poetry published.[18] By that time he had decided to stay in London: he enjoyed his friendship with D. H. Lawrence; continued to have poetry and reviews published; and the American critics were taking notice of him. He began to write a series of Canzone in December as Yeats returned to Dublin.[19]

In 1910, Pound returned to the United States for a year. His arrival in New York coincided with the publication of The Spirit of Romance, of which a Boston critic wrote, "Pound is a man of clear insight ... But to find himself, he must first get lost."[20] He convinced H.D. to join him in New York, but she was unable to find work and returned to Philadelphia, although she promised to visit in Europe if he were to return.[21] Walter Morse Rummel, whom he had met the previous spring in Paris, arrived for a visit and invited him to return to Paris to collaborate on a project to set troubadour poetry to music.[22] On 22 February 1911, Pound sailed from New York, and did not return to the United States for 28 years.[23]

In Paris, he studied at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, finished the Guido Cavalcanti and Arnaut Daniel translations begun in New York, and worked on the Canzoni and the collaboration with Rummel.[24] His interest in music developed as he began to focus on the role of rhythm and pitch in poetry.[25] The friendship with Margaret Cravens (whom he had met a year earlier) continued, and it was during this period that she gave him a large sum of money to fund his writing career.[note 2][26]

After returning to London in August, Pound began work on Ripostes, hoping for publication in February.[27] At this time he was influenced by T.E. Hulme, who claimed that a great artist was one who "dives down into the inner flux of life and comes back with a new shape which he endeavors to fix".[28] Hulme introduced Pound to A.R. Orage, the editor of The New Age, who hired him to write a weekly column.[29] H.D. arrived in London and decided to stay. Pound introduced her to his friends; she found herself attracted to Richard Aldington, who shared her interest in Hellenism. Pound, Aldington and H.D. spent their days in the British Library Reading Room, discussing literature in the tea room in the afternoons. There they decided to start a movement in poetry.[30] By early 1912 Pound referred to H.D. and Richard Aldington as des imagistes and to their poetry as Imagisme.[25] Imagisme, as Pound defined it, adhered to the following tenets:

I. Direct treatment of the "thing"—whether subjective or objective

II. To use absolutely no word that does not contribute to the presentation

III. As regarding rhythm: to compose in sequence of the musical phrase, not in sequence of metronome.[31]

A further definition of Imagism appeared in Ripostes, finally published in October 1912. Imagisme, Pound wrote, "is concerned solely with language and presentation".[32] In August 1912, Harriet Monroe asked Pound to be a regular contributor to Poetry magazine and to act as foreign correspondent. He readily agreed, telling her that he represented Imagisme poets. Between late 1912 and December 1913 he submitted to the magazine poems by himself, H.D, Aldington, Yeats, Robert Frost, D.H. Lawrence, and James Joyce.[33] The Imagist movement began to attract attention from critics; in 1913 Pound collected work for an anthology of Imagisme poets titled Des Imagistes, published in February 1914.[34] According to biographer A. David Moody, the Imagisme movement, of which Pound said "began certainly at Church Walk with H.D., Richard and myself",[35] peaked in 1913, at a period when "all three had rooms at Church Walk".[30]

When Yeats won the 1913 Poetry prize, he gave the money to Pound who used it to buy a typewriter and to commission a sculpture from his friend Henri Gaudier-Brzeska.[36] Gaudier told Pound: "It will not look like you ... It will be the expression of certain emotions which I get from your character."[37] Pound spent the first of three winters with Yeats in 1913–1914 as his secretary. From Yeats, Pound learned that in folklore a multicultural perspective could be found, and, according to Pound scholar George Bornstein, the two pushed one-another towards modernism.[38] Of greater importance was Pound's work on Ernest Fenollosa's papers and translations of Japanese poetry and Noh plays given to him by his widow to organize.[39] Eventually, Pound used Fenollosa's work as a starting point for what he called the ideogrammic method.[40] Pound contributed to Wyndham Lewis' literary magazine BLAST, the first issue of which appeared in June 1914. With its bright cover art and bold lettering, the magazine received a mixed reception: some critics hated it, while others praised the avant-garde style.[41] When a poet called for the rejection of Imagism and a return to the traditionalism of Wordsworth, Pound challenged him to a duel on the basis that "Stupidity carried beyond a certain point becomes a public menace."[42]

During this period, Amy Lowell—an American poet from a wealthy Boston family—arrived in London, searching for Imagist poets to include in an anthology. She accepted work from H.D., Yeats and others, but she refused to include Pound. When critics began to describe Lowell as the "foremost member of Imagists" following the publication of the anthology, Pound was deeply resentful. He began to refer to Imagism as "Amygism", and was further disgusted when his submission to Poetry for T.S. Eliot's "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" was rejected on the basis of being too cosmopolitan.[43] In July 1914 Pound declared Imagisme dead, asking only that the term be preserved, although Lowell eventually anglicized it.[44] He took the concept of Imagism, extended it, and called it Vorticism: "a VORTEX, from which, and through which, and into which ideas are constantly rushing."[44]

On 20 April 1914, Pound married Dorothy Shakespear, despite opposition from her father who was concerned about Pound's idiosyncratic nature and lack of financial stability. Her father relented, however, when the couple agreed to a church rather than a civil ceremony.[45][note 3] Pound and his new wife moved into an apartment at 5 Holland Place, with H.D. and the recently married Aldington as neighbors.[46] Although the couple planned to honeymoon in Spain that September, the outbreak of World War I forced them to postpone. They instead lived with Yeats at Stone Cottage for the winter, where Pound worked on proofs for the second issue of BLAST.[47]

World War I and aftermath

In 1915, Pound published Cathay, a small volume of poems[48] well received by critics. However, he increasingly saw himself as an outsider and added to Cathay a defense of Fenollosa's translations: "I give only these unquestionable poems" for otherwise "it is quite certain that the personal hatred by which I am held by many, and the invidia which is directed against me because I have dared openly to declare my belief in certain young artists will be brought to bear on the flaws of such translations".[49] He secured the patronage of attorney and art collector John Quinn, and made it his mission to promote Lewis, Eliot and Joyce. After Lewis was sent to the front, Pound concentrated on supporting Joyce and Eliot. He helped publish Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Eliot's "Prufrock",[50] and in 1917 had Quinn pay for Joyce's glaucoma operation.[51]

The war deeply affected him, and in July 1915 was criticized for featuring a piece in BLAST about a recently killed—but alive when Pound wrote—poet. A month earlier, Pound had been devastated when Gaudier was killed in the trenches.[52] In April 1916, he published Gaudier-Brzeska: A Memoir which included letters, illustrations, and photographs of Gaudier-Brzeska's work.[48]

When the publication of Lustra was stopped in 1917 because of the perceived immorality of the poetry that "was considered unsuitable for the innocent Young Person and the right-thinking Family", Pound refused suggested revisions. Instead the volume was published as a "private edition" that June.[53] During this period Pound was working on what he referred to as his "long poem". He turned to Browning for inspiration, and by early 1917 sent to Poetry for publication the first three Cantos of his long poem.[54]

He was now a regular contributor to three magazines. From 1917, he wrote music reviews for The New Age under the pen name of William Atheling, and submitted weekly pieces to The Little Review and Egoist, often writing two to three articles each week. The topics were varied: he called for better education in the United States; he began to write about economics; discovered and reviewed a French folk singer; and continued to translate Daniel Arnaut. However, he became disillusioned and exhausted, and thought he was wasting his time with prose. When the Comstock Laws were applied to The Little Review, suppressing the October issue for perceived vulgarity, and again applied to stop the serialization of Joyce's Ulysses, he blamed American provincialism. In September 1917, Hulme was killed by shell fire in Flanders. The Arnaut manuscript was lost at sea and he became sick in 1918—presumably with the Spanish influenza. When the Armistice was signed in November, his response was "Thank God the war is mostly over".[55]

World War I shattered his belief in modern western civilization, to the extent he considered art had not survived the war. Hulme and Gaudier had been killed and Lewis severely wounded. Pound suspected the Vorticist movement itself was finished.[56] In 1919, he collected and published his essays for the Little Review into a volume titled Instigations,[57] and published in "Homage to Sextus Propertius" in Poetry .[58] "Homage" is considered an example of modernism rather than a strict translation; as Moody describes it, the work is "the refraction of an ancient poet through a modern intelligence". Harriet Monroe submitted the translation to a Latin professor who told her Pound was "incredibly ignorant of Latin". Monroe decided to publish only the "more decorous parts". Outraged, Pound ended his association with her.[59] He continued to write cantos, and quickly finished three more. By the winter of 1920 he had enough material to collect into a single volume to be called Poems 1918–1921.[60] His articles for New Age during this period include a series in which he attacks the perceived enemies of artistic enlightenment: nationalism, capitalism, and organized religion.[61] It was in the New Age offices that Pound first met Major C.H. Douglas, from whom he learned about social credit.[62]

During the war Pound had kept Joyce solvent as he finished Ulysses, despite that they had never met. In June 1920, he convinced Joyce to join him in Italy; Joyce was living in poverty and considering returning to Ireland. Pound gave him a suit, traveled with him to Paris, provided introductions and rented lodgings for the family.[63] Six months later, Pound and Dorothy themselves moved to Paris.[64] Orage wrote in the New Age of Pound's departure: "Mr. Pound has been an exhilarating influence for culture in England ... however, Mr. Pound ... has made more enemies than friends. Much of the Press has been deliberately closed by cabal to him; his books have for some time been ignored or written down; and he himself has been compelled to live on much less than would support a navvy."[65]

Hugh Selwyn Mauberley marked a farewell to Pound's London career. Published in 1920, Hugh Selwyn Mauberley conveyed both his rejection of British society and reaction to World War I. Disgusted by the lives lost during the war, Pound was unable to reconcile his beliefs against a society which placed "economic gain at the expense of art".[14] The poems in the first half of the book present a sharp social criticism; those in the second half of the volume focus on a single 'representative' poet—Hugh Selwayn Mauberly—whose life becomes increasingly sterile and meaningless. The consequences of the war were catastrophic as far as Pound was concerned; in Hugh Selwyn Mauberley he manifested a break with his life in London, and with his previous writing style. [14]

Paris

A number of young writers were emerging in Paris. Pound biographer Hugh Kenner writes: "[Paris] was if anything, a Printing Vortex. Books were cheap to produce in France." The custom printing house Three Mountains Press printed and published works by Hemingway, Williams and Pound; Joyce's Ulysses was finally printed by an avant-garde French printer. By 1925, a folio edition of Pound's A Draft of XVI Cantos was printed and released.[66] Eliot visited the city in 1921 with the 40 page manuscript of The Waste Land; Pound patiently blue-inked the piece with comments such as "too easy", "make up yr. mind" and cut three long passages from the poem.[67] He later described himself as a "sage homme" (male midwife) of the poem.[68] When Joyce published Ulysses in 1922, Pound rejoiced and wrote reviews for both "The Waste Land" and Ulysses.[69]

He became friendly with Marcel Duchamp, Tristan Tzara, Fernand Léger and others of the Dada and Surrealist movements.[66] He shared a hotel room with Dorothy before renting a studio at 70 bis rue de Notre Dame des Champs, a small street near the Dôme Café.[70] He turned to carpentry, and built furniture for his studio as well as bookshelves for Shakespeare and Company.[69] Following a letter of introduction from Sherwood Anderson, Hemingway and his wife Hadley were invited for tea with the couple. Hadley found Dorothy's manners intimidating, while Ernest considered their apartment as "poor as Gertrude Stein's studio was rich".[70] Hemingway described Pound as "tall, with a scratchy red beard, fine eyes and strange haircuts".[71] Pound wanted boxing lessons; but as Hemingway told Sherwood Anderson, "[Pound] habitually leads with his chin and has the general grace of a crayfish of crawfish".[72] They toured Italy together in 1923 and lived in the same street in 1924.[72] During their 1923 Italian trip, Hemingway had Pound visit Italian battlefields and explained to him the tactics of Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, in whom Pound found a hero to add to his Cantos.[73]

Pound was 36 when he met the woman with whom he would have a love affair for the next 50 years.[74] At Natalie Barney's weekly musical salon, he arrived one night in the fall of 1922 escorting a young singer. There he met concert violinist Olga Rudge. Glamorously dressed in a red jacket embroidered with gold dragons, Olga was attracted to his looks, charisma and eyes, of which Barney wrote: "Cadmium? amber? no, topaz in Chateau Yquem".[75] Olga and Pound moved in different social circles: the daughter of a wealthy Youngstown steel family, she lived in her mother's Parisian apartment on the Right Bank, and socialized with aristocrats; whereas he moved in the circle of the impoverished writers of the Left Bank. Despite their disparities, Olga entranced Pound with her intelligence and musical ability.[76] The following year, they summered in southern France, where Pound introduced her to "the land of the troubadours".[77] Under her influence he became interested in music, composing two operas, working with George Antheil to apply the concepts of Vorticism to music. Helped by Agnes Bedford, a pianist from London, Pound picked out the rhythm of troubadour poetry; Bedford was surprised at his musical sensibility and the way in which his seemingly unrelated pieces fitted together.[78] During this period he wrote music reviews for the Transatlantic Review, which were later collected into Antheil and the Treatise on Harmony.[79]

He continued to work on The Cantos, writing the bulk of the "Malatesta Sequence" in this period. They introduce one of the major personas of the poem and reflect his preoccupations with politics and economics. The four cantos of the "Malatesta Sequence" were published in The Criterion, with two further cantos published in the first issue of Ford's transatlantic review issued in 1924.[79] Pound secured the funding from Quinn for the transatlantic review, which published works from Pound, Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, and Joyce's Finnegans Wake before running out of funds in 1925.[80]

Italy

In 1924 Pound left Paris for Italy to recuperate after suffering from appendicitis.[81] He and Dorothy stayed in Rapallo briefly, moving on to Sicily, and then returning to settle in Rapallo in January 1925.[82] He established two homes: one with Dorothy and one with Olga.[14] Pound accompanied Olga to the Italian Tyrol, where she gave birth prematurely to their daughter Mary on 9 July 1925.[83] Dorothy was separated from Pound for much of that year and the next: she joined her mother in in Siena in the autumn; and visited Egypt from December 1925 to March 1926. She returned from Egypt pregnant.[84] She wanted the child to be born at the American Hospital in Paris, and had Hemingway take her to the hospital on the afternoon of 10 September 1926 when her son Omar was born.[85] Neither child was raised with their parents: Mary was taken into foster care in the Tyrolean village Gais while Omar was sent to Olivia to be raised in England. [82] Yeats moved to Rapallo in 1928; the following year Homer and Isabel sold their belongings and moved to Italy to join their son.[86]

| So far, we have Pound the major poet devoting, say, one-fifth of his time to poetry. With the rest of his time he tries to advance the fortunes ... of his friends. He defends them when they are attacked, and gets them into magazines and out of jail. He loans them money. He sells their pictures. He arranges concerts for them .... He advances them hospital expenses and dissuades them from suicide. |

| — Ernest Hemingway tribute to Ezra Pound 1925.[87] |

In 1925, the newly launched literary magazine, This Quarter, was dedicated to Pound with the first issue including tributes from Hemingway and Joyce. Pound published Cantos 17, 18, and 19 in the winter editions.[88] Shortly thereafter he stopped writing for about 18 months, although he was busy during this period: his opera Le Testament de Villon was performed in Paris; he became interested in the writings of John Reed; and prepared for publication Collected Poems 1926.[89]

In 1927, Pound's hope for launching a literary magazine was realized when The Exile went to press in March 1927.[90] According to biographer James J. Wilhelm, "Pound's journal burned brightly" during its first year, with contributions from Hemingway, E. E. Cummings, Basil Bunting, Yeats, William Carlos Williams and Robert McAlmon. With the exception of his own Canto XXIII, Wilhelm claims the poorest writing came from Pound himself, in the form of rambling editorials about Confucianism, and that here "the seeds of religious intolerance were clearly showing roots".[91] Only four issues of the magazine were published.[82] Pound continued to work on Fenellosa's manuscripts, and in 1928 won the Dial poetry of the year award for the translation of the Confucius poem Ta Hio.[82] A limited edition (200 copies) of Pound's Cantos XXX was published in 1930. At age 44 he had devoted 15 years to the work.[92]

In the 1930s Pound came to believe the solution to the economic crisis of the Great Depression was social credit;[93] and that rapid economic reform was required to prevent another war.[94] He became convinced that left-wing fascism presented the means to implement reform, although was annoyed that Mussolini's fascism was underestimated, and that his friends perceived him "as an apologist for Mussolini and facist Italy".[95] Pound scholar Leon Surette notes that Pound turned to contemporary books to gain insight into economic theory, yet this led to confusion because "orthodox economics of his day had no solution for the disaster of the world depression".[93] His correspondence shows a shift in his ideas on economics, usury, towards antisemitism.[96] Determined to spread the message of economic reform, he presented a series of lectures about economics,[97] before becoming drawn into politics. Convinced he had the ability to effect real change, he contacted politicians in the United States with policies on areas such as education, interstate commerce and international affairs.[98]

Olga met Mussolini in 1927, and she was impressed with his knowledge of modern art. As a result Pound rejoiced that in Italy he had found a government that treated artists with importance.[99] Against advice from Hemingway, on 30 January 1933 Pound met with Mussolini and within weeks began work on The ABC of Economics, and Jefferson and/or Mussolini.[100] In 1935 the Italian government asked him to give a series of radio speeches on the subject of "the economic triumph of fascism";[101] and when in 1936, the Ministry of Propaganda again offered Pound a weekly radio broadcast, he refused, saying "I don't care a hoot about talking over the radio".[96]

In 1936, James Laughlin—who earlier as a 20-year-old student had visited Pound in Rapallo in 1933—started his publishing company New Directions.[82] He acted as agent for Pound, finding publications to accept his work, and writing reviews of Pound's work. At the end of the decade he acquired the rights to The Cantos, and published Cantos LII–LXXI in 1940, although Pound refused his demand to excise anti-semitic content.[102] According to Wilhelm, Pound's burgeoning anti-semitism became most apparent in Canto 34.[103] A number of Pound's books were published in the 1930s, including an American edition of A Draft of Cantos XXX, Eleven New Cantos, the English edition of The ABC of Reading, English editions of Social Credit: An Impact and Jefferson and/or Mussolini; and in 1938 A Guide to Kulchur.[104]

Dorothy's mother Olivia Shakespear died in October 1938. Ill and unable to travel, Dorothy asked her husband, who was in Venice with Olga and Mary, to go London, organize the funeral, clean out the house, and provide care for their son Omar. At the funeral 12-year-old Omar met his father for the first time.[105] During his month-long stay in London while visiting Eliot, Lewis and other old friends, Pound talked about a possible return to the United States. Upon his return to Italy he first traveled to Rome with Olga and Mary, and then sailed for New York, with the intention of stopping American involvement in World War II.[106] Pound traveled directly to Washington, D.C., where he met with cabinet members, senators and congressmen. He offered his services to Senator Borah to work for the country in an official capacity. According to biographer Noel Stock, "Pound was depressed because he was not having the success in Washington that he thought he might have".[107] He left Washington to receive an honorary Ph.D from Hamilton College. A week later he returned to Italy.[108] At the outbreak of World War II in September, Pound began a furious letter-writing campaign to the politicians he had petitioned six months earlier: the war, he claimed, was the result of an international banking conspiracy and usury, and the United States should "keep out of it".[109]

World War II

By 1939 Pound's writing became increasingly antisemitic.[110] A year later he translated Italy's Policy for Social Economics for Odon Por which he believed was a good example of the implementation of social credit in Italy.[111] Because he felt his efforts to thwart the war and his economic philosophy were being ignored, he approached Rome Radio with the idea of making weekly radio broadcasts.[112] Stock notes that by 1940 Pound was living in isolation he believes Pound may have felt alone intellectually, a man obsessed with his ideas. He was geographically isolated from his homeland—and England—by virtue of living in an Axis country.[110] For the first time in decades he faced the necessity to earn a living: Dorothy's income stopped coming from England; Homer's pension checks arrived late or not at all; and his royalty checks were stopped because of the war.[113]

In September 1940, he considered leaving Italy, but as he wrote a friend, "thought of going to U.S. to annoy 'em, but Clipper won't take anything except mails until Dec. 15. So am back here at the old stand."[114] In 1941, Pound tried on two separate occasions to leave Italy with Dorothy: on the first he was denied passage on by plane,[115] the second time they were refused on a diplomatic train out of the country.[116] The prospect of leaving, with his mother, his father (who was disabled from a recent hip fracture), his wife, his lover and his daughter (who did not have an American passport), was becoming increasingly difficult.[117] In February 1942, his father Homer died.[118]

| Pound speaking, and I think I am perhaps speaking a bit more to England than to the United States .... They say an Englishman's head is made of wood and the American head made of watermelon. Easier to get something into the American head but nigh impossible to make it stick there .... I don't know what good I'm doing. |

| — Portion of December 7 1941 radio broadcast from Italy.[119] |

From 1941 to 1943 Pound made 100 radio broadcasts from Rome to America on shortwave,[120] with a two month interlude after the United States entered the war in December 1941.[121] In the broadcasts, Pound was critical of the United States, President Roosevelt, and showed his antisemitism.[115] Pound scholar Ira Nadel explains that in the Rome broadcasts Pound supported Mussolini and Hitler, and he "developed a litany of antisemitic attitudes and remarks".[122] However, he often rambled about subjects such as his poetry, economics and Chinese philosophy, to the point that "the Italians suspected him of being an American agent."[123] Pound scholar Wendy Flory believes from as early as 1935 Pound suffered from a mental illness, manifested in the pronounced antisemitism of the radio broadcasts. She sees the broadcasts as "disorganized rantings reflecting his confused and delusional attitude".[124] He pre-recorded the 10 to 15 minute broadcasts, received about $18 for each one that aired, and received a free rail pass to travel from Rapallo to Rome. The broadcasts were monitored by the Foreign Broadcast Monitoring Service of the United States government, and transcripts, now stored in the Library of Congress, were made of them.[125] Pound was indicted in absentia for treason by the United States government in 1943.[118]

When the Allied forces landed in Sicily in July 1943 Pound was in Rome. Worried about his daughter Mary's safety in German occupied Tyrol, he borrowed a sturdy pair of boots, and walked approximately 450 miles north to see her.[126] When Pound found Mary he chose at that time to admit he had a wife, and a son who lived in London.[127] He stayed long enough for his feet to heal, but was at risk for arrest by the police, and soon returned south to Olga and Dorothy.[126] In 1944 Pound and Dorothy were evacuated from their Rapallo home. Pound intended to leave Dorothy in Rapallo to look after his mother Isabel, and to join Olga in Sant'Ambrogio. Instead, Dorothy chose to live with Pound and Olga, leaving Isabel in Rapallo. Olga took a job in an Ursuline school; Dorothy who had not learned Italian after almost two decades in the country was forced to learn to shop and cook.[128]

On 2 May 1945, when Dorothy and Olga were out on errands, armed partisans arrived while Pound was at work on a translation. He stuffed the copy of Confucius in his pocket and allowed himself to be taken "to their HQ in Chiavari, where he was soon released as possessing no interest". He demanded to be taken to the Americans, and was brought to the U.S. command in Lavagna. The next day the F.B.I interrogated him in Genoa.[129] Safe and well-fed at Counter Intelligence Corps headquarters, Pound requested permission to contact President Truman via telegram to offer his assistance in negotiations with Japan (given his knowledge of Japanese culture); and to be allowed to finish a prepared radio broadcast that called for a post-war policy of leniency toward Italy and Germany. His requests were denied and the material for the broadcast forwarded to J. Edgar Hoover.[130]

On 24 May, he was transferred from Genoa to a United States Army Disciplinary Training Center (DTC) north of Pisa. He was the only civilian in the camp and treated as a war criminal.[131] Because he was considered a suicide risk, for 25 days he was kept in an open steel cage to allow observation where, it is believed, he suffered a nervous breakdown. While in the cage he had only the copy of Confucius. Later he was transferred to a tent where for a period he was "deprived of all reading matter but religious tracts". He underwent three psychiatric evaluations, was given reading material and began to write again. He drafted the Pisan Cantos in the camp. The existence of a few sheets of toilet paper on which the beginning of Canto LXXXIV is written has led to speculation that he began the poem while still in the cage.[132]

On 15 November 1945, Pound was transferred from Italy to the United States. One of the escorting officer's impression of Pound was that "he is an intellectual 'crackpot' who could correct all the economic ills of the world and who resented the fact that ordinary mortals were not sufficiently intelligent to understand his aims and motives."[132]

St. Elizabeths

| [Ezra] is obviously crazy .... He deserves punishment and disgrace, but what he really deserves is ridicule. He should not be hanged and he should not be made a martyr of .... It is impossible to believe anyone in his right mind could utter the vile and utterly idiotic drivel he has broadcast. |

| — Ernest Hemingway on Pound's incarceration at St. Elizabeths.[133] |

On 25 November 1945, Pound was arraigned in Washington D.C. on charges of treason. The list of charges included broadcasting for the enemy, attempting to persuade American citizens to undermine government support for the war, and strengthening morale in Italy against the United States. Pound was unwell at the reading and remanded to a Washington D.C. hospital where he underwent psychiatric evaluation. A week later he was admitted to St. Elizabeths hospital and assigned to a lunatic ward until February 1947. Unable to renew her passport, Dorothy was unable to travel until June, from when her 'legally incompetent' husband was placed in her charge. She was allowed infrequent visits until his move to Chestnut Ward the following year—the result of her legal appeal—after which she was able to spend several hours with him each day. He began to correspond and receive visitors including Olga Rudge, while Mary—now married—began to translate his work into Italian.[134]

During 1946 and 1947, he submitted portions of the Pisan Cantos to a number of literary magazines for publication. Laughlin published a full edition in 1948 and Faber published a second edition in 1949.[135] In 1948 the first Bollingen Prize for Poetry was awarded to Pound for his Pisan Cantos. Nadel claims "no book of twentieth-century American poetry created more controversy than the Pisan Cantos", with the public outraged at the award of a prize to a convicted fascist and antisemite.[136] He continued his translation of Confucius, which were published in 1950.[137] By the mid-1950s, Pound's privileges were increased and he received visitors including Robert Lowell, William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky. Olga Rudge visited during 1952; Mary a year later, spending the time with her father helping to organize his work.[138] Stock claims Pound was then "more widely appreciated than any other time".[138][139] In 1954, Pound was considered for a Nobel Prize in Literature—the year Hemingway won—with Hemingway remarking it "would be a good year to release poets".[138]

For many years, Archibald MacLeish and Eliot fought to have Pound released.[140] Robert Frost and Ernest Hemingway helped in the effort, which stalled after white extremist John Kasper decided to run an "Ez for Prez" campaign. Hemingway believed asking Pound to stop making political statements was futile; he told MacLeish he "could see the media all too easily needling Pound into racist statements". Nevertheless, Hemingway believed Pound should be released and was willing to give him $1,500.[141] In 1958, an attorney took the case and requested dismissal of the indictment. It took the jury minutes to decide to release him.[140]

Both his insanity plea and incarceration at St. Elizabeths Hospital continue to be controversial. E. Fuller Torrey believes he received special treatment from Winfred Overholser, the superintendent at St. Elizabeths. According to Torrey, Overholser admired Pound's poetry and allowed him to live in a private room at the hospital, where he wrote books, received visits from literary figures and enjoyed conjugal relations with his wife.[142] Pound scholar Wendy Flory disagrees. Although she concedes that a reflective analysis of Pound's actions may be construed as apologist, she argues against the notion that national antisemitism can be mitigated by the idea of Pound as "National Monster".[121] She writes, "A commonly held conspiracy theory explains that, with the connivance of the superintendent of St. Elizabeths, Pound faked insanity to avoid possible execution. In fact his medical records, letters and the testimony of many visitors to St. Elizabeths, show clear evidence of psychosis, as this is now defined."[143] Tim Redman, author of Ezra Pound and Italian Fascism, does not believe in a conspiracy at St. Elizabeths, but does agree with Torrey's theory that "Pound's insanity plea was concocted by his friends".[144]

Return to Italy and death

Pound arrived with Dorothy in Naples on 9 July 1958, where he was photographed giving a fascist salute by the waiting press.[145][146] He and Dorothy lived with Mary at Castle Brunnenburg near Merano, in Bolzano-Bozen—where he met his grandchildren for the first time—and then later returned to Rapallo.[147]

By December 1959, he suffered from depression, insisted his life's work was worthless, and The Cantos were "botched". A move to Rome brought a brief respite.[148] In a 1960 interview given in Rome to Donald Hall for Paris Review, Pound explained much about his life. He claimed to have conceived the idea for The Cantos as early as 1905, and discussed the difficulty of living in London on a small income. He described a childhood memory of "the sight of money being shoveled at the Philadelphia Mint", and admitted progress on The Cantos was stuck while his health was poor.[149]

A few months later he was admitted for a brief stay in a clinic near Brunnenberg. In July 1961 after refusing to eat, he was returned to the clinic. When he learned Olga and Mary were readmitting him he was furious. His behavior worsened a few days later when he was told of Hemingway's suicide, when he "went into a terrible tantrum, said American writers were all doomed, and the USA destroys all of them, especially the best of them".[150] He was diagnosed with prostate and urinary problems, and moved to Rapallo for medical care. According to Wilhelm, Dorothy was too frail to continue tending her husband, and Olga took over. From 1962 until his death he lived with her.[150] Flory believes Pound's mental breakdown was a manifestation of his psychosis, which had been temporarily held in check during his incarceration at St. Elizabeths. However those close to him attribute the breakdown to senile dementia.[148] Whatever the cause, Pound clung to life for another decade, which he attributed to Olga's influence.[74]

A year later, William Carlos Williams died, followed two years later by T.S. Eliot. Pound attended Eliot's funeral in London and during the trip traveled to Dublin to visit Yeats's widow. He continued to travel and to give public poetry readings during this period. He met with Allen Ginsberg in 1967, who visited him in Rapallo. Two years later he traveled to New York for the opening of an exhibition featuring Eliot's manuscript of The Waste Land he had blue-inked.[147]

On his return to Italy, he moved with Olga to Venice where he lived the last years of his life, mostly in silence, writing very little, and growing increasingly frail. In the last week of October 1972 he and Olga attended a Noh play and a production of Midsummer Night's Dream. A few days later he was too weak to leave his bedroom to celebrate his birthday. The following night Olga had him brought to the hospital.[151]

Ezra Pound died in Italy on 1 November 1972, at 87, and is buried on the island cemetery of San Michele in Venice. The following year Dorothy died in London. Olga Rudge died in 1996 and is buried next to Ezra.[147]

Themes and style

| "In a Station of the Metro" The apparition of these faces in the crowd: Petals, on a wet, black bough. |

| — an example of Pound's minimalist imagism.[152] |

Opinion varies on the style of Pound's poetry. Critics generally agree that he was a strong lyricist, as particularly evident in his early poetry.[153] Scholars see evidence of modernism in his poetry as early as the 1912 Ripostes.[154] He drew on literature varying from medieval troubadour and ancient Chinese poetry to contemporary traditions.[155] Nadel believes Pound found in Imagism a foundation on which to build, and by which to reject Victorian poetic traditions: "Imagism evolved as a reaction against abstraction ... replacing Victorian generalities with the clarity in Japanese haiku and ancient Greek lyrics."[156] Pound wanted his poetry to represent an "objective presentation of material which he believed could stand on its own" without use of symbolism or romanticism.[157] It was in the Chinese writing system that he found what he most closely wanted. He used Chinese ideograms to represent "the thing in pictures", and from Noh theater learned how unity and image eclipsed plot.[158] In its purest form Imagism was a form of minimalism, represented by his two-line poem "In a Station of the Metro". However Minimalism did not lend itself to the epic, so Pound turned to the more dynamic structure of Vorticism for The Cantos.[159]

The Cantos are difficult to define and to decipher. They are filled with "cryptic and gnomic utterances, dirty jokes, obscenities of various sorts".[153] Nadel argues they should be read as an epic, that is "a poem including history", and that the "historical figures lend referentiality to the text". The Cantos function as contemporary memoir, in which "personal history [and] lyrical retrospection mingle", an idea most clearly represented in the Pisan Cantos.[160] Michael Ingham sees an American tradition of experimental literature in The Cantos, of which he writes: "These works include everything but the kitchen sink, and then add the kitchen sink".[161] Pound mixes satire, diaries, hymns, elegies, essays, memoirs and more, and breaks the boundaries of literary genres in The Cantos.[160] Furthermore, The Cantos rely on the use of ideogrammic translation, and the incorporation of up to 15 different languages. In The Cantos, Pound layered ideas, cultures, and historical periods, through the juxtaposition of modern vernacular, Classical languages, and underlying truths, often represented with Chinese ideograms.[162]

Yet a common criticism of The Cantos is their lack of form and coherence.[163] Pound himself felt a lack of form to be their great failure, and said "I cannot make it cohere".[164] Similar to Herman Melville's Moby Dick, Pound redefined the nature of poetic translations for the 20th century, according to Pound scholar Ming Xie of the University of Beijing. Xie explains that Pound's first translation, of the Old English poem "The Seafarer", attracts either condemnation or defense. Xie argues that Pound's use of language in the translation is extremely deliberate, in order to avoid merely "trying to assimilate the original into contemporary language". Neither Pound nor Fenollosa spoke or read Chinese proficiently, and Pound has been criticized for omitting or adding sections to his poems which have no basis in the original texts, though critics argue that the fidelity of Cathay to the original Chinese is beside the point.[165] In his chapter "The Invention of China" from The Pound Era, Kenner contends that Cathay should be read primarily as a work about World War I, not as an attempt at accurately translating ancient Eastern poems.[166]

Pound's relationship to music is integral to an understanding of his poetry. From his study of troubadour poetry, written to be sung and incorporating a "motz et son", Pound came to believe all poetry should be written similarly.[167] In his essays, Pound wrote of rhythm as "the hardest quality of a man's style to counterfeit".[168] He compared the form of The Cantos to a fugue. Ingham argues that in form The Cantos do not adhere to that of a fugue, although they can be defined as fugal in nature with multiple themes presented simultaneously and interrupted by unrelated themes. Moreover, he sees the incorporation of counterpoint as integral to the structure and cohesion of The Cantos.[169]

Legacy

| The three Cantos are not easy reading ... They are like an old Italian slope, where the very earth speaks of warriors and singers and lovers whose dust it is. They echo, they are haunted. |

| — 21 July 1918 New York Times review of Lustra.[170] |

Pound was in part responsible for advancing the careers of some the best-known modernist writers of the early 20th century. He befriended, helped, and influenced T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, Wyndham Lewis, Robert Frost, William Carlos Williams, H.D., Marianne Moore, Ernest Hemingway, D. H. Lawrence, Louis Zukofsky, Jacob Epstein, Basil Bunting, e.e. cummings, George Oppen and Charles Olson.[171] Pound scholar Hugh Witmeyer goes so far as to say that the Imagist movement "is the most important movement in English language poetry of the twentieth century", because every prominent 20th-century poet has applied imagist theories and practices.[172]

Beyond his influence on the Imagist movement, Pound's legacy and reception are mixed. The Cantos have been described as a "shifting heap of splinters", and its "twisted forms" as nearly impossible to read. Eliot felt the need to publish an explanation of the Cantos as early as 1917; Zukofsky published another in 1929; and Laughlin added an explanation to Cantos LIII–LXXI in 1940. Conversely, The Cantos have been seen as a great achievement in 20th-century poetry with "syntax yielding to parataxis".[173] Hugh Kenner said "there is no great contemporary writer who is less read than Ezra Pound".[174] Peter Nichols, of the University of Sussex, believes a central facet of Pound's achievement is that his "work has suggested different paths to different poets".[175] The 1960s and '70s saw a Pound retrospective, when critics such as Donald Davie and Hugh Kenner brought a new appreciation to his reputation and work. However, Michael Alexander writes in The Poetic Achievement of Ezra Pound that "in Britain a wider appreciation of his ... poetry has not yet arrived", whereas in the United States, Pound scholarship is quite strong. Alexander believes Pound's full achievement has not yet been established; the body of his work continues to be studied and defined, but particularly in Britain it has yet to be made accessible.[176]

| Perhaps no English poem since the time of Alexander Pope has stirred so much fuss as the Pisan Cantos ... however, the poem in this case in not so much the thing as the unsavory political history of its author. |

| —excerpt from August 1949 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article about the Bollingen Prize controversy.[177] |

Pound's antisemitism is central to an evaluation of his poetry and even whether his poetry will be read. The outrage at Pound was so deep that the imagined method of his execution—hanging or shooting—dominated the discussion.[178] Arthur Miller considered Pound worse than Hitler: "In his wildest moments of human vilification Hitler never approached our Ezra ... he knew all America's weaknesses and he played them as expertly as Goebbels ever did".[179] Angry condemnation continues to be a prevalent response to Pound the person and Pound the poet. The response went to so far as to denounce all modernists as fascists, and not until the 1980s have critics begun a re-evaluation of Pound. In her essay "Pound and antisemitism" Wendy Flory argues that Pound, to some extent, represented an ingrained but unacknowledged national antisemitism, and his vilification as "National Monster" mitigated national guilt. She claims that Pound's antisemitism served "as a convenient placeholder for all those whose antisemitism was not being confronted".[180]

The Pisan Cantos won the first Bollingen Prize—administered the first and last time by the Library of Congress—in 1949, to much controversy; the media claimed that the award equated to support for antisemitism.[181] In August 1949, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette quoted critics who said of Pound's poetry that it "'cannot convert words into maggots that eat at human dignity and still be good poetry'"; and the article claimed that "art today cannot be divorced from political sentiment".[177][note 4] Those who contested the prize believed the spirit of New Criticism had been taken too far. Flory's view is that the best way of examining and analyzing The Cantos is to separate the poetry from Pound's antisemitism, although she concedes that the approach is perceived as apologetic.[182]

As a translator Pound was a pioneer with a great gift of language and an incisive intelligence.[183] He helped popularize major poets such as Guido Cavalcanti and Du Fu and brought Provençal and Chinese poetry to English-speaking audiences. He revived interest in the Confucian classics and introduced the west to classical Japanese poetry and drama (the Noh theatre). He translated and championed Greek, Latin and Anglo-Saxon classics and helped keep them alive at a time when classical education was in decline, and poets no longer considered translations central to their craft.[184]

Selected list of works

- "Hugh Selwyn Mauberley" (1920)

- ABC of Economics (1933)

- The Cantos

Notes

- ↑ Thaddeus Pound supported the McKinley Tariff, was opposed to the free silver movement, disagreed with laissez-faire ideology, and backed government economic regulation. See Redman 1999, pp. 250–251

- ↑ Margaret Cravens may have given Pound as much as two-thirds of her income, which he kept secret from his family and from Dorothy's family. Cravens committed suicide a year later, after hearing the news of Pound's unofficial engagement to Dorothy and Rummel's engagement to her former piano teacher. She listened to a tune written by Pound and Rummel as she took her life. See Dennis 1999, p. 267

- ↑ The two had been unofficially engaged since 1911, with Dorothy adhering to social convention and waiting for her father's permission to marry. See Dennis 1999, p. 267

- ↑ Paul Mellon of the Pittsburgh banking family donated the funds to the Library of Congress in 1949. A congressional hearing in August 1949 decided to remove the decision-making process from the Library of Congress.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Wilhelm 2008, p. xiii

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 3-4

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 10–11

- ↑ Moody, p. 8

- ↑ Redman 1999, pp. 250–251

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 12-15

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 17–21

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Nadel 2007, pp. 4–5

- ↑ Wilhelm 2008, p. xiv

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 28–34

- ↑ Moody 2007, pp. 59–60

- ↑ Moody 2007, pp. 65–67

- ↑ Wilhelm 2008, pp. 3–11

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Witkoski 2007

- ↑ qtd. in Wilhelm 2008, p. 25

- ↑ O'Connor 1963, p. 8

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 65–67

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 70–74

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 77–80

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 81–89

- ↑ Wilhelm 2008, pp. 57–58

- ↑ Wilhelm 2008, pp. 62–65

- ↑ Stock 1970, p. 95

- ↑ Wilhelm 2008, pp. 67–69

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 O'Connor, pp. 20–22

- ↑ Dennis 1999, p. 267

- ↑ Moody 2007, p. 167

- ↑ Stock 1970, p. 107

- ↑ Wilhelm 2008, p. 80

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Moody 2007, p. 180

- ↑ qtd. in Parini 1995, p. 13

- ↑ Moody 2007, p. 222

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 119–146

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 143–147

- ↑ qtd. in Moody 2007, p. 222

- ↑ Moody 2007, p. 235

- ↑ Stock 1970, p. 146

- ↑ Bornstein 1999, p. 26

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 148–149

- ↑ Nadel 1999, p. 2

- ↑ Stock 1970, p. 161

- ↑ Stock 1970, p. 159

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 164–169

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Moody 2007, p. 224

- ↑ Wilhelm 2008, p. 153

- ↑ Moody 2007, pp. 249

- ↑ Wilhelm 2008, p. 154

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Stock 1970, p. 174

- ↑ Moody 2007, p. 266

- ↑ Moody 2007, pp. 278–284

- ↑ Sieburth Poems, p. 1215

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 180–182

- ↑ Moody 2007, pp. 285–290

- ↑ Albright 1999, pp. 59–62

- ↑ Moody 2007, pp. 330–342

- ↑ Moody 2007, p. 355

- ↑ Moody 2007, p. 343

- ↑ Moody 2007, p. 349

- ↑ Moody 2007, pp. 349–353

- ↑ Moody 2007, pp. 387–388

- ↑ Moody 2007, p. 369

- ↑ Moody 2007, p. 372-375

- ↑ Moody 2007, pp. 394–396

- ↑ Moody 2007, p. 409

- ↑ qtd. in Moody 2007, p. 410

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Kenner 1973, p. 384

- ↑ Bornstein 1999, pp. 33–34

- ↑ Bloom 1986, p. 57

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Stock 1970, pp. 245–250

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Carpenter 1988b, p. 65

- ↑ Meyers 1985, p. 70–74

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Meyers 1985, pp. 70–74

- ↑ O'Connor 1963, p. 35

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Walters, Colin (November 4, 2001). "Old Ez and his Faithful Violinist". The Washington Times.

- ↑ Conover 2001, pp. 1–3

- ↑ Wilhelm 1994, p. 241

- ↑ Carson 2001, p. 4

- ↑ Kenner 1973, p. 390

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Stock 1970, pp. 252–256

- ↑ Carpenter 1988a, pp. 430-431

- ↑ Carpenter 1988, p. 437

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 82.3 82.4 Nadel 1999, pp. xxii–xxiii

- ↑ Carpenter 1988a, p. 448

- ↑ Carpenter 1988a, pp. 449-451

- ↑ Carpenter 1988a, pp. 452-453

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 274–280

- ↑ qtd. in Stock 1970, p. 260

- ↑ Stock 1970, p. 260

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 260–265

- ↑ Wilhelm 1994, pp. 20–21

- ↑ Wilhelm 1994, pp. 22–24

- ↑ Stock 1970, p. 289

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Surette 1999, p. 2

- ↑ Nadel 1999, p. 10

- ↑ Redman 1991, pp. 156–158

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Redman 1991, p. 170

- ↑ Stock 1973, pp. 301–314

- ↑ Stock 1973, p. 295

- ↑ Wilhelm 1994, p. 22

- ↑ Stock 1973, pp. 306–307

- ↑ Redman 1991, pp. 156–158

- ↑ Tryphonopoulos 2005, p. 176

- ↑ Wilhelm 1994, p. 99

- ↑ Sieburth Poems, pp. 1222–1223

- ↑ Wilhelm 1991, pp. 136-138

- ↑ Wilhelm 1991, pp. 139-142

- ↑ Stock 1970, p. 362

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 360-365

- ↑ Stock 1970, p. 368

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 Stock 1973, p. 371

- ↑ Stock 1973, p. 390

- ↑ Carpenter 1988, p. 583

- ↑ Carpenter 1988, p. 587

- ↑ qtd. in Stock 1973, p. 383

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 Nadel 1999, p. xxv

- ↑ O'Connor 1963, p. 43

- ↑ Wilhelms 1994, p. 184

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 Nadel 1999, p. xxvi

- ↑ O'Connor1963, p. 5

- ↑ O'Connor1963, p. 6

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 Flory 1999, p. 284

- ↑ Nadel 1999, p. 11

- ↑ O'Connor1963, p. 43

- ↑ Nadel 1999, p. 20

- ↑ Wilhelm 1994, pp. 177–179

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 Stock 1973, pp. 400–401

- ↑ Wilhlem 1994, p. 203

- ↑ Wilhelm 1997, pp. 206–207

- ↑ Kenner 1973, pp. 470–471

- ↑ Sieburth 2003, p. x

- ↑ Sieburth 2003, pp. xii–xiii

- ↑ 132.0 132.1 Kimpel 1981, pp. 470–474

- ↑ qtd. in Meyers 1980, p. 514

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 417–422

- ↑ Stock 1970, pp. 424–424

- ↑ Nadel 2007, p. 17

- ↑ Stock 1970, p. 428

- ↑ 138.0 138.1 138.2 Stock 1970, pp. 435–437

- ↑ He was also visited by Hugh Kenner, whose The Poetry of Ezra Pound was published in 1951, and was influential in the reassessment of his poetry. See Stock (1970), 428

- ↑ 140.0 140.1 Stock 1970, pp. 445–447

- ↑ Reynolds 2000, p. 303

- ↑ Mitgang, Herbert. "Researchers dispute Ezra Pound's 'insanity'. New York Times, October 31, 1981. Retrieved on February 25, 2008.

- ↑ Flory 1999, pp. 286–287

- ↑ Redmund 1991, p. 6

- ↑ Stock 1970, p. 449

- ↑ "Pound, in Italy, Gives Fascist Salute; Calls United States an 'Insane Asylum' (subscription required)". The New York Times. July 10, 1958. pp. 56. http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=FA0E12FF3C5F117B93C2A8178CD85F4C8585F9. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ↑ 147.0 147.1 147.2 Nadel 2007, p. 18

- ↑ 148.0 148.1 Flory 1999, p. 296

- ↑ Wilhelm 1994, pp. 331–332

- ↑ 150.0 150.1 Wilhelm 1994, pp. 333–335

- ↑ Wilhelm 1994, pp. 333–335

- ↑ qtd. in Albright 1999, p. 60

- ↑ 153.0 153.1 O'Connor 1963, p. 7

- ↑ Witemeyer 1999, p. 47

- ↑ Nadel 1999, p. 1

- ↑ Nadel 1999, p. 2

- ↑ Nadel 1999, p. 2

- ↑ Nadel 1999, p. 3

- ↑ Albright 1999, p. 60

- ↑ 160.0 160.1 Nadel 1999, pp. 1-6

- ↑ Ingham 1999, p. 240

- ↑ Ming 1999, p. 217

- ↑ Nadel 1999, p. 8

- ↑ Nicholls 1999, p. 144

- ↑ Ming 1999, pp. 204–212

- ↑ Kenner 1971, p. 199

- ↑ Ingham 1999, pp. 236–237

- ↑ Pound 1968, p. 103

- ↑ Ingham 1999, p. 244

- ↑ "Ezra Pound, Poet of the state of Idaho". The New York Times Book Review. The New York Times. 21 July 1918. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9C02E5DA143EE433A25752C2A9619C946996D6CF. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ↑ Bornstein 1999, pp. 22–23

- ↑ Witmeyer 1999, p. 48

- ↑ Nadel 1999, pp. 8–9

- ↑ qtd. in Nadel 1999, p. 13

- ↑ Nichols 1999, p. 264

- ↑ Alexander 1998, pp. 15–18

- ↑ 177.0 177.1 "Canto Controversy" Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. August 22, 1949. Retrieved 2010-08-07.

- ↑ Flory 1999, p. 285

- ↑ qtd. in Flory 1999, p. 285

- ↑ Flory 1999, pp. 285–286

- ↑ Stock 1970, p. 426

- ↑ Flory 1999, pp. 294–295

- ↑ Alexander 1997, p. 208

- ↑ Alexander 1997, pp. 23–25

Sources

- Albright, Daniel (1999). "Early Cantos: I – XLI". In Nadel, Ira. The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64920-X. http://books.google.com/?id=XU0kKuU4IVMC&dq=isbn=052164920X.

- Alexander, Michael (1997). "Ezra Pound as Translator". Translation and Literature (Edinburgh University Press) 6 (1): 23–30.

- Bloom, Harold (1986). T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land. New York: Chelsea House.

- Bornstein, George (1999). "Ezra Pound and the making of modernism". In Nadel, Ira. The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64920-X. http://books.google.com/?id=XU0kKuU4IVMC&dq=isbn=052164920X.

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1988a). A Serious Character: the life of Ezra Pound. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-41678-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=_t0EAQAAIAAJ&dq=isbn:0395416787&cd=1.

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1988b). Geniuses Together: American Writers in Paris in the 1920s. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-46416-1.

- Conover, Anne (2001). Olga Rudge and Ezra Pound. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08703-9. http://books.google.com/books?id=tc8FEiAiNtIC&dq=olga+rudge&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

- Dennis, Helen M. (1999). "Pound, women and gender". In Nadel, Ira. The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64920-X. http://books.google.com/?id=XU0kKuU4IVMC&dq=isbn=052164920X.

- Flory, Wendy (1999). "Pound and Antisemitism". In Nadel, Ira. The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64920-X. http://books.google.com/?id=XU0kKuU4IVMC&dq=isbn=052164920X.

- Hyde, Lewis (1983). "Ezra Pound and the Fate of Vegetable Money". Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property. Vintage Bookss. ISBN 0-394-71519-5.

- Ingham, Michael (1999). "Pound and music". In Nadel, Ira. The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64920-X. http://books.google.com/?id=XU0kKuU4IVMC&dq=isbn=052164920X.

- Kenner, Hugh (1973). The Pound Era. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520024274.

- Kimpel, Ben D.; Eaves, Duncan (1981). "More on Pound's Prison Experience". Ameican Literature (Duke University Press) 53 (1): 469–476. doi:10.2307/2926232.

- Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

- Ming, Xie (1999). "Pound as tranlator". In Nadel, Ira. The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64920-X. http://books.google.com/?id=XU0kKuU4IVMC&dq=isbn=052164920X.

- Moody, David A. (2007). Ezra Pound, Poet: The Young Genius 1885–1920. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199215577. http://books.google.com/?id=ynycfEXsUqwC&dq=Moody,+A.+David+(2007).+Ezra+Pound:+Poet+I:+The+Young+Genius+1885-1920..

- Nadel, Ira, ed (1999). The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64920-X. http://books.google.com/?id=XU0kKuU4IVMC&dq=isbn=052164920X.

- Nadel, Ira, ed (2007). The Cambridge Introduction to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521853910. http://books.google.com/?id=jHxpxheAHOMC&dq=isbn=9780521630696.

- Nicholls, Peter (1999). "Beyond the Cantos:Ezra Pound and recent American poetry". In Nadel, Ira. The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521649209. http://books.google.com/?id=XU0kKuU4IVMC&dq=isbn=052164920X.

- O'Connor, William Van (1963). Ezra Pound. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Parini, Jay, ed (1995). "Introduction". The Columbia Anthology of American Poetry. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08122-7.

- Perloff, Marjorie (1982). "Pound/Stevens: Whose Era?". New Literary History (Johns Hopkins University Press) 13 (3).

- Pound, Ezra (1968). The Spirit of Romance. New York: New Directions. ISBN 0-8112-1646-2.

- Redman, Tim (1991). Ezra Pound and Italian Fascism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37305-02. http://books.google.com/?id=hjJ7uj0zWN8C&dq=ezra+pound's+radio+broadcasts.

- Redman, Tim (1999). "Pound's politics and economics". In Nadel, Ira. The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64920-X. http://books.google.com/?id=XU0kKuU4IVMC&dq=isbn=052164920X.

- Sieburth, Richard (2003). The Pisan Cantos. New York: New Directions Publishing. ISBN 0-8112-1558-X9. http://books.google.com/?id=TubCKx3F6UQC.

- Sieburth, Richard (2003). Poems and Translation. New York: The Library of America. ISBN 1-931082-42-3.

- Stock, Noel (1970). The LIfe of Ezra Pound. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-8654-7075-8.

- Tryphonopoulos, Demetres; Adams, Stephen, eds (2005). The Ezra Pound Encylopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-30448-3. http://books.google.com/?id=ttMlqGMYCsIC.

- Wilhelm, James J. (1994). Ezra Pound: The Tragic Years 1925–1972. University Park, PA: The University of Pennsylvania State Press. ISBN 0-271-01082-7. http://books.google.com/?id=s3mw-IZom4sC&dq=ezra+pound+the+tragic+years.

- Wilhelm, James J. (2008). Ezra Pound in London and Paris, 1908–1925. University Park, PA: The University of Pennsylvania State Press. ISBN 9780271027982. http://books.google.com/?id=UpmBwzOT7hwC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q.

- Witemeyer, Hugh (1999). "Early Poetry 1908–1920". In Nadel, Ira. The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64920-X. http://books.google.com/?id=XU0kKuU4IVMC&dq=isbn=052164920X.

- Witkoski, Micheal (2007). "Pound, Ezra (subscription required)". Magill's Survey of American Literature. Salem Press. http://connection.ebscohost.com/content/. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

External links

- Ezra Pound Papers at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

- Ezra Pound collection at University of Victoria, Special Collections

- Frequently Requested Records: Ezra Pound, United States Department of Justice

- Audio recordings